1 July 2016 | Draft

Criteria Justifying Recounting or Revoting in Democracy post-Brexit

Highlighted by the case of the UK referendum

-- / --

Introduction

Eligibility to vote

Criteria of democratic fairness in voting

Democracy from a future perspective?

Criteria for electoral recount

Criteria for revoting: repeating an election or referendum

Challenging applicability of electoral claims to analogous issues

Dubious rejection of electronic voting

Introduction

It is unclear what systematic consideration is publicly given to the criteria of democratic fairness in referenda and other elections. Little has been said in this respect with respect to the process of Brexit -- the democratic decision of the UK to leave the European Union. In the course of protests regarding that result, it was announced that an even closer result in a major presidential election in Austria had led to a decision to hold the election again.

In the case of Brexit, it is being widely asked (at the time of writing) whether the referendum vote was fair (Petition for second EU referendum reaches 4 million, The Telegraph, 29 June 2016; Are you protesting against Brexit this weekend? The Guardian, 1 July 2016).

There is also doubt as to whether the outcome has been finally and formally decided (Patrick Wintour, UK voted for Brexit -- but is there a way back? The Guardian, 29 June 2016; Philip Allott, Forget the politics -- Brexit may be unlawful, The Guardian, 30 June 2016). The latter argues that there is strong reason to believe that the government's withdrawal decision would be unlawful, and hence that any notification of withdrawal would be invalid.

The point is further emphasized by Ian Johnston (Brexit loophole? MPs must still vote in order for Britain to leave the EU, say top lawyers, The Independent, 27 June 2016) noting the argument of a constitutional lawyer: A new bill to repeal the 1972 European Communities Act that took Britain into the EU must now be passed by parliament... It's the right of MPs alone to make or break laws, and the peers to block them. So there's no force whatsoever in the referendum result. It's entirely for MPs to decide.

It continues to be disputed whether triggering Article 50 requires the authority of parliament. Political and legal necessity may indeed require the endorsement of parliament (Brexit: Legal steps seek to ensure Commons vote on Article 50, BBC News, 4 July 2016; Nick Barber, et al., Pulling the Article 50 'Trigger': Parliament's Indispensable Role, UK Constitutional Law Association, 27 June 2016, fith over 350 comments; Brexit: Letter saying EU referendum result 'not legally binding' signed by 1000 lawyers, The Independent, 11 July 2016). At present, there is not a majority for Britain to leave the EU in either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. Indeed, given a free vote, it is believed that the unelected Lords would probably reject Brexit by a margin of six to one.

Given the seeming absence of criteria, it might be asked what the position would have been had the majority been: 1, 10, 100, 1000 or 10,000 -- as was a matter of concern in Austria. If the number for and against had been equal, what would then have been the conclusion?

Curiously the issue is otherwise highlighted (at the time of writing) by lack of any majority in a vote for membership of the UN Security Council. As a consequence a somewhat surreal resolution has been that two countries would "share the seat" (Netherlands, Italy to Share UN Security Council Seat, Voice of America, 28 June 2016).

In the case of Brexit, it might be asked how -- in a democratic country -- some 48% are expected to accept the right of 52% to leave the EU? And what if it had been 50.1%, or 49.9%? And how are the desires of a majority of voters in one part of the country to be reconciled with those in another part of the country? The question is further highlighted (at the time of writing) by reports of the possibility of a hung parliament in Australia following preliminary results of an election with Labor leading the Coalition on 50.06% to 49.94% on a two-party-preferred basis (Australia Election: tight vote could end in hung parliament, BBC News, 3 July 2016). What are the implications of a "hung referendum" -- a "hung Brexit", for example?

Most provocative is the question whether arguments of similar quality apply for the UK to "leave" other intergovernmental arrangements deemed by significant proportions of the electorate to be of questionable value. Brexit NATO? This would be consistent with the initiative of General de Gaulle in 1966.

Knowing that the current global system is increasingly inadequate to respond to many human crises, there is increasing conviction that environmental justice often overlaps with social justice. Equally provocative is then the case for new international institutions and laws to give a voice to ecosystems and non-human forms of life, as argued by Anthony Burke and Stefanie Fishel (Politics for the Planet: why nature and wildlife need their own seats at the UN, The Conversation, 30 June 2016). A suggestive precedent is indicated by United Animal Nations, founded in 1979.

Eligibility to vote

A valuable summary of this issue was provided prior to the Brexit referendum by Alberto Nardelli (Britain's EU referendum: who gets to vote is a potential deciding factor, The Guardian, 13 May 2015). In discussing who gets to vote, this notes that:

The question over who will be able to cast a ballot in the EU referendum is far more complicated than may initially meet the eye. In last week's UK parliamentary general elections British citizens, and qualifying Commonwealth citizens and citizens of the Republic of Ireland resident in the UK were, if registered, eligible to vote. These same criteria were used in the 2011 AV referendum. However, citizens of EU countries residing in the UK can vote in elections for local government and the European parliament. And, following the precedent set by the Greater London Authority, EU citizens can also vote in elections for the Scottish parliament, the National Assembly for Wales, and the Northern Ireland Assembly if they are registered in Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland respectively.

Nardelli notes further with respect to the Brexit referendum that:

If the same criteria as in the general British parliamentary election were used then there would be about 46 million eligible voters. Of these, about 3.4 million are born in Commonwealth countries, British overseas territories/crown dependencies and Ireland -- meaning that if a criteria based on nationality were adopted instead (like Ireland did for its vote on the Nice Treaty, and does for constitutional referendums, for example) the number of eligible voters could drop to as low as 42.6 million (the precise number would depend on how many are also British citizens as they would still be able to cast a ballot).

The right (and desirability) of any "diaspora" also to vote was discussed with respect to the referendum on the independence of Scotland from the UK (Affinity, Diaspora, Identity, Reunification, Return: reimagining possibilities of engaging with place and time, 2013). The question raised was the nature of the identification of those in distant countries with a country such as Scotland. A similar question is relevant with respect to the Brexit referendum, namely the sense in which some in the UK consider themselves to be "European", irrespective of their formal relationship to Britain.

Criteria of democratic fairness in voting

The question of fairness is usefully summarized by an entry in Wikipedia on Voting Systems. This notes that:

Those who are unfamiliar with voting theory are often surprised to learn that voting systems other than majority rule exist, or that disagreements exist over what it means to be supported by a majority. Depending on the meaning chosen, the common "majority rule" systems can produce results that the majority does not support. If every election had only two choices, the winner would be determined using majority rule alone. However, when there are more than two options, there may not be a single option that is most liked or most disliked by a majority. A simple choice does not allow voters to express the ordering or the intensity of their feeling. Different voting systems may give very different results, particularly in cases where there is no clear majority preference.

The entry distinguishes:

- Multiple-winner methods

- Proportional methods, summarized separately (Proportional representation)

- Semi-proportional methods

- Majoritarian methods

- Single-winner methods, as summarized separately (Single-winner voting systems)

The summary includes a discussion of Evaluating voting systems using criteria. Several criteria of fairness are specifically addressed. Those noted are:

- Majority Criterion: Any candidate receiving a majority of first place votes should be the winner.

- Mutual majority criterion: Namely whether a candidate will always win who is among a group of candidates ranked above all others by a majority of voters -- with the implication of a Majority loser criterion

- Condorcet Criterion: Namely whether a candidate will always win who beats every other candidate in pairwise comparisons

Other criteria include:

- Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives Criterion: If an election is held and a winner is declared, this winning candidate should remain the winner in any recalculation of votes as a result of one or more of the losing candidates dropping out.

- Independence of Clone Alternatives

- Monotonicity Criterion: If an election is held and a winner is declared, this winning candidate should remain the winner in any revote in which all preference changes are in favor of the winner of the original election. A ranked voting system is monotonic if it is neither possible to prevent the election of a candidate by ranking them higher on some of the ballots, nor possible to elect an otherwise unelected candidate by ranking them lower on some of the ballots (while nothing else is altered on any ballot).

- Consistency criterion

- Reversal symmetry

| Compliance of selected voting systems (Reproduced as an image from Wikipedia entry on Voting systems) |

|

| Comparison of single-member district election methods (reproduced as an image from Wikipedia entry on Single-member district) |

|

Democracy from a future perspective?

Why is it so readily assumed that democracy itself will not be imagined otherwise in the decades and centuries to come?

There is of course the question whether democratic voting, as currently practiced, is inherently flawed in some fundamental manner -- making it significantly "unfit for purpose" in a period of crisis of governance (Paul Craig Robert, The Collapse of Western Democracy, Global Research, 1 July 2016; Destabilizing Multipolar Society through Binary Decision-making, 2016).

The latter draws attention to non-binary frameworks, one of which could be interpreted with respect to Brexit (in terms of a tetralemma) as: Leave, Remain, Leave-And-Remain, Neither-Leave-Nor-Remain. It could be said that, in practice, the UK has already explored variants of the last two conditions over past decades.

Rather than focus on "membership", together these four conditions could be understood as framing a degree of flexibility which is precluded from conventional understanding of options. They might otherwise be considered as offering a means of reframing the currently intractable Israel/Palestine issue, for example. Familiarity with the two seemingly "illogical" additional conditions is currently evident in any contractual arrangement, whether economic or most obviously that of marriage (or those within the LGTB communities). The approach could be extended to reframing the issue of the "in" or "out" status of migrants, as is partially evident to those with multiple passports and tax obligations (Brexit: Dual nationality on the table for Britons? BBC News. 4 July 2016).

With respect to debate preceding any vote, as with the Brexit referendum, there is extensive commentary on its problematic nature. The future may see the merit of the binary distinction between what has been characterized as the reasoning of a "soldier" in contrast to that of a "scout" -- as presented in a recent TED talk by Julia Galef (Why you think you're right -- even if you're wrong, February 2016). Both engage in motivated reasoning.

In the case of the soldier, this is goal-oriented motivated reasoning based on an assumption of knowledge of what is right -- thereby ignoring as irrelevant information which does not accord with that assumption. As a form of confirmation bias, it enables action -- including the proverbial readily-to-be-found simple solution to a complex problem. By contrast, the scout engages in accuracy-oriented motivated reasoning, characterized by curiosity as to the reality of a situation, however much it may be unpleasant and challenge the most fundamental assumptions. Brexit was effectively a demonstration of both modes, but with little ability to distinguish between them. The same might be said of the strategic response to terrorism and other intractable issues (Global Incomprehension of Increasing Violence: matching incapacity to question the reason why, 2016).

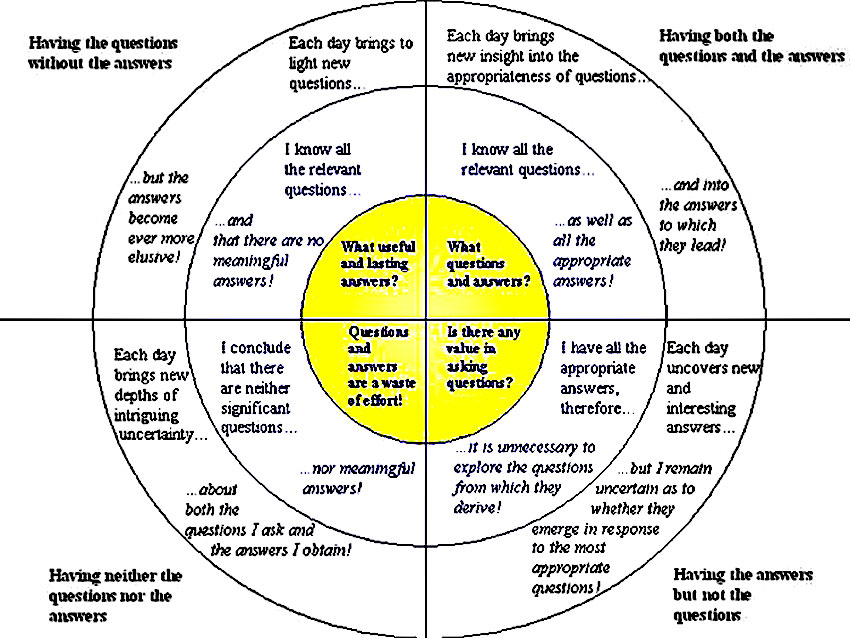

In effect democracy-as-practiced is the challenging encounter between "answers without questions" and "questions without answers". Missing is any consideration of the need for "both question and answer" and "neither question nor answer". A somewhat similar recognition was evident in the notorious response by Donald Rumsfeld as US Secretary of Defense during the Iraq war. It concerned the relation between: the known knowns, the known unknowns, the unknown knowns, and the unknown unknowns -- as separately discussed (Unknown Undoing: challenge of incomprehensibility of systemic neglect, 2008). The fourfold pattern can be succinctly represented diagrammatically

| Democracy as the challenging encounter between answers and questions? (reproduced from Sustaining the Quest for Sustainable Answers, 2003) |

|

Ironically it is increasingly recognized that the combination of computer gaming and artificial intelligence is engendering new insight with potential implications for governance (Karen Schrier, Knowledge Games: how playing games can solve problems, create insight, and make change, 2016). A review of the latter notes their potential relevance to the solution of the intractable wicked problems of governance (Douglas Heaven, Can video games really create new knowledge? New Scientist, 25 May 2016).

Such examples suggest that artificial intelligence and neural learning, benefitting from the records of online gaming strategies of millions, may enable discovery of unsuspected patterns of considerable significance to democratic governance -- in terms of their memorability, credibility, and despite their complexity (Michael A. Nielsen, Neural Networks and Deep Learning, Determination Press, 2015).

Are there more appropriate voting systems yet to be discovered? Who is encouraged to look for them? Why is greater attention not given to such possibilities -- notably with respect to such dramatic decisions as Brexit?

Criteria for electoral recount

There are many instances of an election recount, notably for local rather than national elections. This is requested, and used, to determine the correctness of an initial count. Recounts will often take place in the event that the initial vote tally during an election is extremely close. It is also recognized that errors can be found or introduced from human factors, such as transcription errors, or machine errors, such as misreads of paper ballots.

Claims are frequently made for a recount as a consequence of electoral fraud or vote rigging -- as extensively discussed by Wikipedia. As noted there:

Recounts can be mandatory or optional. In some jurisdictions, recounts are mandatory in the event the difference between the top two candidates is less than a percentage of votes cast or of a fixed number. Mandatory recounts are paid for by the elections official, or the state. Mandatory recounts can usually be waived by the apparent losing candidate. The winning side will usually encourage the loser to waive the recount in a show of unity and to avoid spending taxpayer money.

Can it be proven (or disputed) that the Brexit referendum was free from electoral fraud? Framed in a menner more pertinent to the current conflict of interests, how much would it have cost to rig the vote, who might have been prepared to pay that price, and can it be unequivocably demonstrated that this was not the case? Given the lies widely acknowledged to have characterised the campaign, is it not appropriate to envisage such a possibility -- however much it may be denied by those appreciative of the result?

The currently embarrassing condition of democracy is that those with the power to engage in fraudulent voting practices have no way of proving with any credibility that they have not done so. They can only appeal for confidence, despite the widespread sense that has been abused (Ian McEwan, Britain is changed utterly -- unless this summer is just a bad dream, The Guardian, 9 July 2016).

Criteria for revoting: repeating an election or referendum

There is seemingly less information on the criteria for revoting -- in contrast with recounting votes already cast. As noted above in the case of the Austrian presidential election in 2016, it was deemed appropriate to vote again rather than recount, due to the nature of the irregularities.

There is now a call for second Brexit referendum (Eric Zuesse, Why There Will Probably Be a Second Referendum on Brexit, Global Research, 1 July 2016; Jon Stone, Second Brexit referendum Early Day Motion put to Parliament, The Independent, 1 July 2016; Doug Bandow, A Brexit Revote? The American Spectator, 1 July 2016). The latter addresses the question: Just when should the majority -- and what kind of a majority -- rule?

Possible criteria for a revote might include:

- natural disaster on voting day (or prior to it), preventing many from voting or disrupting electoral procedures. The issue in this case would be what constitutes a "natural disaster" determining the need for a revote. Clearly many such disasters are relatively localized, even though formally declared to affect the population as a whole in some measure. Hurricane Katrina offers an extreme example -- as might extensive wildfires. However torrential rain affecting transportation and the capacity (or willingness) of voters to travel to voting stations presumably merits consideration -- but to what degree? An unusual level of rainfall was notable on Brexit voting day in the UK in some areas. Could this be said to invalidate the fairness of the vote in some constituencies?

- major accidents on voting day, most notably affecting transportation systems and the capacity (or willingness) of voters to travel to voting stations.

- massive electoral fraud (on a scale beyond that noted above) may take forms which justify a revote rather than a recount.

- valid majority, as is recognized in some jurisdictions, there is the question of what percentage of majority can be considered as unquestionably indicative of the preference of the electorate -- in contrast with a percentage which can be readily subject to climate, shifting movements of opinion, and other temporary factors?

- significant misrepresentation of facts by candidates and their parties with regard to the issues at stake. This was notably evident in the Brexit campaign and gave rise to formal protest by the EU (Bethan McKernan, 8 of the most misleading promises of the Vote Leave campaign, Indy100, 24 June 2016; Katie Collins, Brexit campaign wipes its homepage amid accusations of false promises, CNet, 27 June 2016; Roger Cohen, Britain to Leave Europe for a Lie, The New York Times, 27 June 2016; Vanessa Baird, Stop Brexit-fuelled racism and campaign lies, New Internationalist, 29 June 2016). The case is now being made for an appropriately "informed democratic vote" (Geraint Davies, A second EU referendum could pull us out of the fire, The Guardian, 30 June 2016).

It is of course the case that there is tolerance of the capacity of candidates for election to present promises which they have no intention of fulfilling. Information can also be presented as factual and may be challenged in debate. The question is at what point the misrepresentation amounts to deliberately misleading the electorate. The issue is evident in the case of consumer advertising where puffery and boosterism is considered acceptable, but false and deceptive advertising is subject to prosecution.

At what point can a widely circulated. factually misleading, electoral manifesto justify the demand for a revote? This is especially the case if any incitement to racism can be legally challenged (Adam Taylor, The Uncomfortable Question: Was the Brexit vote based on racism? The Washington Post, 25 June 2016)

- misrepresentation by omission might under some circumstances be considered cause for a revote. In retrospect, this could be considered evident in the case of the vote in the UK Parliament with regard to intervention in Iraq, following the submissions to the UN Security Council in 2003. In both arenas it has emerged that those called upon to vote had been deliberately deceived and misled through the nature of the "facts" presented -- as has yet to be fully clarified by the forthcoming publication of the report Chilcot Inquiry.

In the case of Brexit a valuable example is offered by the strong emphasis placed on loss of jobs by the Leave campaign -- at a time when it had been otherwise announced that millions of jobs were anyway to be lost in the immediate future as a consequence of automation. In contrast to the stressed need for protection from incoming migrants, almost no mention was made of the threat to jobs from "home grown" robots, as otherwise discussed (Robots threaten 15m UK jobs, says Bank of England's chief economist, The Guardian, 12 November 2015; Timothy Torre, Robots could replace half of all jobs in 20 years, TechTimes, 24 March 2015; Michael Osborne, 47% of jobs may be taken by robots, Science Interviews, 24 March 2016).

There is even a possibility that such a questionable "democratic process" will be shortly used by NATO to decide on whether to engage in a war with Russia and its allies -- a democratically engendered World War III (Michel Chossudovsky, Towards a World War III Scenario: the dangers of nuclear war, Global Research, 31 March 2016; US-NATO Aggression and the Risk of World War III: selected articles, Global Research, 19 May 2016).

As with misselling, at what point does the "nastiness" of negative campaigning justify revoting, as might follow from the arguments of Jay Elwes (A National Trauma, Prospect, 25 June 2016). Misselling is the deliberate, reckless, or negligent sale of products or services in circumstances where the contract is either misrepresented, or the product or service is unsuitable for the customer's needs. The subprime mortgage crisis resulted from just such misselling by the insurance and real estate industries -- leading to the global financial crisis of 2007-2012.

Can misselling be compared with the abuse of confidence now recognized in the case of the Brexit campaign? Could the pattern of misdirection by leading Brexiteers even be compared with that caricatured by the expression snake oil salesmen -- offering a panacea for the ills of British society, before disappearing after the successful sale? Will this even come to be recognized in their subsequent affirmations that the referendum result was conclusive in determining the withdrawal of the UK from the EU -- if constitutional law concludes otherwise (Nigel Farage resigns as UKIP leader after 'achieving political ambition' of Brexit, The Guardian, 4 July 2007).

Presumably extreme care will be taken to avoid the disastrous process of misdirection -- to be clarified by the Chilcot report -- through which the UK government decided to support the USA in the intervention in Iraq in 2003 (Legality of the War in Iraq, Wikipedia). Given its controversial role at that time, any formal opinion by the Attorney General for England and Wales regarding Brexit will now be examined with the greatest of attention (Attorney General's Advice on the Iraq War Iraq: Resolution 1441, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 2005; Attorney General '50/50' on Brexit, Solicitors Journal, 15 February 2016; Jon Stone, Second EU referendum would be possible, former attorney general says, The Independent, 4 July 2016).

Insightful comparison between Brexit and UK decision to invade Iraq? |

|

| Chilcot report conclusions (2003-2016) | Brexit report conclusions (2016-2029) ? |

|

|

Commentaries by The Economist (The Chilcot report: Iraq's grim lessons, 6 July 2016), indicate that the official inquiry into the war delivers a scathing verdict on its planning, execution and aftermath: That lack of caution, combined with a disregard for process that bordered on the feckless, was a recurring theme in the run-up to the war. The learnings from the inquiry are related to Brexit in the lead editorial:

Yet it also carries a risk that the wrong lesson may be learned. As Britain begins the tortuous, regrettable process of disentangling itself from the rest of Europe, it is already in danger of turning inward. The Chilcot report will be read by many not merely as evidence of a badly conceived mission, thinly planned and poorly executed, but as proof that Britain and its Western allies should hasten their retreat from the wider world. That would be bad for all who share those countries' liberal values. (The dangerous chill of Chilcot, The Economist, 6 July 2016).

Following recent acknowledgements regarding the illegality of the Iraq war (Iraq war 'was illegal', Blair's former deputy acknowledges, RT, 10 July, 2016), it is curious to note parallels implied by the declaration of the newly installed chairman of the UK Conservative Party, Patrick McLoughlin, that although the EU referendum result is not legally enforceable:

I'm quite clear that the referendum result is binding on Parliament. Technically it isn't, but I'm clear that it is binding on Parliament. (Peter Yeung. Brexit: Article 50 will be triggered before next general election, The Independent, 24 July 2016)

In the light of the Chilcot Report, the argument could however be reversed. Whether the referendum result is legally binding or not, morally it would seem to be wise to seek the assent of Parliament, rather than assume that it could be readily bypassed. The pattern of subsequent announcements continue to suggest parallels with the intervention in Iraq as reviewed by the Chilcot Report:

- Theresa May 'acting like Tudor monarch' over plans to deny parliament Brexit vote (The Independent, 28 August 2016)

- Theresa May could start Brexit process without vote by MPs, Government lawyers reportedly say (The Independent, 28 August 2016)

- Brexit: EU referendum result 'not legally binding', say more than 1,000 lawyers (The Independent, 11 July 2016)

- Brexit vote was not binding so parliament must decide, lawyers tell PM (The Independent, 11 July 2016)

- Parliament should make final decision on whether to leave EU, barristers say (The Guardian, 11 July 2016)

- UK will never leave EU because the Brexit process is 'too complex' (The Independent, 29 August 2016)

- 2nd Brexit referendum 'may be justified', says ex-attorney general (RT, 5 July 2016)

- Parliament may be able to block full Brexit, admits David Davis (The Independent, 13 September 2016)

- Theresa May has to ignore the House of Lords on Brexit -- but she does so at her own peril (The Independent, 14 September 2016)

- Government forced to release 'secret arguments' for triggering Article 50 ahead of legal challenge against Brexit (The Independent, 28 September 2016)

- House of Lords future at risk if it tries to block Brexit, leading cabinet minister warns (The Independent, 22 October 2016)

- UK Government agreed referendum could not be legally binding (The Independent, 17 October 2016)

When does a "big lie" give cause for revoting, as can be variously explored (Existential Challenge of Detecting Today's Big Lie, 2016). By what decision-making processes is "democratic oversight" on critical issues ensured within the bodies responsible? One-man-one-vote?

The post-Brexit emphasis on "radical reform" by Theresa May , as the new UK prime minister, is noted separately (Radical Innovators Beware -- in the arts, sciences and philosophy: terrifying implications of radical new deradicalisation initiative in France, 2016). There is now the delightful irony that the antagonistic French perspective on Brexit could be framed by them in terms of that newly announced French approach to "deradicalisation". The UK could then prove to be an appropriate concern of the EU Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN) -- effectively suggesting a "healthy" deradicalisation of the EU through the exclusion of the UK. The UK could thus be justifiably "purged" from the EU due to its radical tendencies.

Challenging applicability of electoral claims to other issues

Brexit international membership? In the case of the Brexit referendum, the arguments made by the Leave campaigners merit consideration in terms of the applicability of their criteria to other international arrangements in which the UK has long been involved.

The further irony to the pro-Brexit argument for independence from the EU, and reclaiming control of the country, is that many of the points apply equally well to cessation of membership of NATO, OECD, ILO, FAO, UNESCO, and other intergovernmental institutions whose decisions impose constraints on individual countries such as the UK.

In deciding to "leave" the EU, should this same logic not be applied to leaving the Council of Europe, for example? Is such membership to be recognized -- in terms of "getting our country back" -- as being as much a constraint on portions of the electorate as UK membership of the EU? Furthermore, in deciding to leave the EU, and necessarily its European Parliament, people may have readily confused this with the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe or the Assembly of the Western European Union -- both quite distinct bodies -- from which the UK should clearly withdraw in fulfillment of that same desire for independence.

Brexit NATO? Should such cases now be subject to referenda -- a Brexit NATO, for example -- if only by default, or consequent on the independence of Scotland? (Kim Sengupta, What does Brexit mean for Trident, intelligence and national security? The Independent, 3 July 2016; John Andrews, NATO After Brexit, Project Syndicate, 2 July 2016; Giulia Paravicini, Britain can leave NATO, too, Politico, 4 July 2016).

Other than Article 13, there does not appear to be any equivalent in the North Atlantic Treaty to the provisions of the much-cited Article 50 by which the UK would initiate its withdrawal from the EU. However a noted precedent is the withdrawal of France from NATO's military structure in 1966. This was initiated by General de Gaulle in order to give France an independent defence force. All French armed forces were removed from NATO's integrated military command, and all non-French NATO troops were asked to leave France. A series of secret accords between US and French officials (the Lemnitzer-Ailleret Agreements) detailed how French forces would dovetail back into NATO's command structure should East-West hostilities break out (Edward Cody, After 43 Years, France to Rejoin NATO as Full Member, The Washington Post, 12 March 2009).

Subsequent to Brexit, it has been remarkable to note the many arguments for the UK to "remain" in NATO -- curiously reminscent of the arguments of the original Remain campagin (NATO Says UK To Stay 'Strong' Ally Despite Brexit, Defense News, 24 June 2016; Why Nato is more important than the EU for Britain, The Spectator, 14 May 2016). These contrast with the few resembling those of the Leave campaign, with the notable exception of those of a US presidential nominee (Trump says US may abandon automatic protections for Nato countries, BBC News, 21 July 2016; Trump says US may not automatically defend Nato allies under attack, The Guardian, 21 July 2016).

On the other hand even the possibility of the EU leaving NATO has now been raised (Jed Babbin, Will EU exit NATO after Brexit? The Washington Times, 3 July 2016).

Brexit Scotland? The argument for independence clearly also applies from the perspective of other regions within the UK, such as Scotland or the City of London -- which notably voted overwhelmingly to "remain" (Independence of Scotland from a Crimean Perspective: emerging strategic logic of the new century understood otherwise? 2014; James O'Malley, Declare London independent from the UK and apply to join the EU). Concernhas been expressed that such regions ran the risk of being "done over" by the UK-EU negotation process (Steve Morris, Scotland, Wales and N Ireland could demand vote on Brexit terms, The Guardian, 22 July 2016).

Concerned with any precedent for their own secessionist regions, it is for this reason that France and Spain have expressed their opposition to a negotiated arrangement of Scotland with the EU.

Emulation by other governments? In the aspiration to be "great" again, governments could well seek to get "out" of many painfully negotiated intergovernmental agreements, as indicated by the pronouncements of an American presidential candidate (Donald Trump would 'cancel' Paris climate deal, BBC News, 27 May 2016; Donald Trump vows to cancel Paris agreement and stop all payments to UN climate change fund, The Telegraph, 27 May 2016; Trump vows to reopen, or toss, NAFTA pact with Canada and Mexico, Reuters, 28 June 2016).

Dubious rejection of electronic voting

In a period in which millions engage in online computer games of ever increasing complexity, democratic voting could be deemed to be of a level of simplicity which could well be characterized as obsolete. Arguably it is in urgent need of an "upgrade" appropriate to the facilities and demands of a much-acclaimed information society.

This is further suggested by the dependence of policy-making on opinion polls and ratings -- many of which are conducted electronically, as with the increasingly influential role of social media in electoral campaigns. Ironically the anti-Brexit protests acquired focus through an e-petition organized in days at little cost -- in contrast to the time and considerable cost of organizing the Brexit referendum. Questions regarding its reliability are equally relevant to other internet transactions (How online bots conned Brexit voters, The Washington Post, 27 June 2016; Brexit: How to Hijack Democracy Online, Newsweek, 1 July 2016).

The disconnect is curiously exemplified by the manner in which citizens are increasingly obliged (with every verbal assurance) to conduct their financial transactions via the internet -- denying the relevance of all issues of age, competence and connectivity. It is also curiously exemplified by the constrained use of technology in legislative assemblies -- themselves significantly characterized by absenteeism on the part of representatives of the people (The Challenge of Cyber-Parliaments and Statutory Virtual Assemblies, 1998).

There is however the strange irony that there is no implication that the quality of democratic voting could be enhanced through electronic voting (see also the summary of electronic voting by country). This is especially justified in response to the levels of voter apathy, notably amongst those who make most intensive use of the internet (Addressing Youth Abenteeism in European Elections, League of Young Voters in Europe, 2014). These are partly due to the inconvenience of transportation to a voting station and queuing -- notably for the physically impaired, the home-bound, and those otherwise constrained in their movement (or simply having other priorities).

Postal voting is only admissible under very particular conditions, if at all. Little is heard of the European CyberVote project, launched by the European Commission in 2000 with the aim of demonstrating "fully verifiable on-line elections guaranteeing absolute privacy of the votes and using fixed and mobile Internet terminals" (An innovative cyber voting system for Internet terminals and mobile phones, 2000-2003). A recent study commissioned and supervised by the European Parliament's Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs makes no mention of it (Potential and Challenges of e-Voting in the European Union, 2016).

Are democratic societies now witness to the "institutionalization of inconvenience" in the name of democracy -- deprived of the possibility of voting in the comfort of their own homes or wherever they choose to be (as is now the case with internet usage)? At what stage does the formal requirement to use the internet for purposes of tax declaration enable the insistence on physical voting to be challenged as a strange form of confidence trick? Why not provide the options of physical voting, postal voting and electronic voting -- as has been the case with financial transactions?

There is a curious contradiction between the purportedly greater reliability of a physical vote and that called into question with regard to the security of internet financial transactions. This is remarkable -- given the degree to which people are personally dependent to a high degree on the security of such transactions for the management of their assets. If it is only the reliability of physical voting that can be guaranteed, what is to be said of claims regarding the reliability of financial transactions? The argument could be developed further in that both are indicative of the collective and individual management of confidence -- as with tax declarations.

One of the great advantages of electronic voting is that results could be presented for comparison and discussion in the light of a variety of voting systems -- variously emphasizing distinct understandings of democratic fairness on which debate could then usefully focus. The expensively cumbersome logistics of physical voting permits no such flexibility. It can be readily understood as biased in favour of those interests which depend on such inadequacies for political advantage. This bears comparison with the dubious process of gerrymandering voting constituencies.

Could the denial of the right to vote electronically now be challenged as a form of "electoral fraud" in its own right? With regard to Brexit, does this suggest the possibility of a case to be brought before the European Court of Human Rights -- before the UK now chooses to further disassociate itself from its rulings (The UK and the European Court of Human Rights, 2012; British judges not bound by European Court of Human Rights, The Guardian, 24 May 2015)? For those in relatively remote areas, is the failure to allow electronic voting to be considered a reprehensible form of discrimination?

In the absence of internet voting, given the discouraging levels of rainfall on the occasion of the Brexit vote, could this be said to invalidate its democratic quality? In addition to the high levels of misrepresentation, are there other significant factors which prevented eligible voters from voting on that occasion?

|

For further updates on this site, subscribe here |